Image Source: Skerryvore (2023). A typical kirana (small store) in Mumbai. These stores make up 88% of the bricks-and-mortar retail market.1

The explosive growth in environmental, social and governance (ESG) data sets, which are available to investors both from third parties and from companies themselves, means that there is a risk that important signals get lost in the increasing noise.

Sustainability reports have burgeoned from pamphlets into novels. However, just because you are able to report something and it can be measured doesn’t always mean it’s important. And companies can easily distract from what really matters by swamping sustainability reports with immaterial charts and figures. This is less blatant than some forms of greenwashing, but is still a persistent problem. Take the example of an Indian power company that buries its carbon emissions at the back of its sustainability report. And it’s not just the quantity of data that can cloud issues, but also the relevance – a Brazilian bank and a Taiwanese chip manufacturer have very different material sustainability issues.

To illustrate Skerryvore’s approach, we will outline our analysis of the material sustainability issues at Hindustan Unilever (HUL). This is a subsidiary of Unilever and the largest fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) company in India. The company is more than 90 years old, has more than 50 brands and is the number-one employer of choice in the country2. We were drawn to the business initially when we discovered that other companies had developed a habit of hiring HUL’s senior people due to their quality – clearly they were doing something right if their people were in such demand. The analysis of the company’s material sustainability issues below formed part of our bottom-up focused research process.

A case study: Hindustan Unilever

We started by comparing what the company identifies as its material sustainability issues with those that we believe to be material. SASB, a standards organisation now under IFRS3, has done some great work in promoting this idea and produced a handy tool to help assess various industries4.

Figure 1 shows HUL’s choice of priority topics. The ones we identified were a smaller subset of these. We focused the weight of our analysis on plastic packaging, emissions, sourcing and management oversight, because we believe these areas will have the greatest material impact on the health of the business over the long term. We discuss each topic in more detail below.

Differentiated sourcing can provide a long-term competitive advantage and reduce reputational risk. Carbon emissions need to be reduced as governments, regulators and consumers will ultimately pass on the external costs of carbon emissions to the producers, just as they will for plastic packaging and its effects on the environment. Therefore, any failure to address these issues now would be likely to impact the long-term operating margins of the business.

Importantly from a visibility perspective, there was no evidence of the company trying to distract us from its sustainability issues – unlike one manufacturer of baby nappies, which did so by excluding waste entirely from its sustainability report.

Figure 1. Hindustan Unilever’s materiality assessment

Plastics

Packaging is a large and growing problem for every FMCG. Around 855 billion plastic sachets are sold globally every year, enough to cover the entire surface of the Earth5. HUL is often credited with popularising sachets in the 1980s, when it sold tiny portions of shampoo for 1 Indian rupee (around 1 US cent) to make personal care products more affordable to a low-income population. By the turn of the century, nearly 70% of shampoo sold in India came in sachets6.

The problem with sachets is that they are normally made of several materials, including plastic and aluminium, bonded together. These layers are costly and difficult to separate, meaning it’s easier to burn or bury sachets than it is to recycle them. The sheer volume of them has created a growing environmental issue that cannot be ignored.

The good news is that the company openly recognises this problem7. HUL is targeting 100% reusable, recyclable or compostable plastic packaging by 2025. This is a big commitment, given the company produces around 120 thousand tons of plastic packaging a year8. As part of a bigger group, HUL also has access to pioneering technologies, such as monomaterial-based sachets, which are under trial in Vietnam, and a recycling facility that can handle sachets in Indonesia7.

The company has already made a significant impact by collecting over 110 thousand tonnes of plastic a year, which is more than the plastic packaging it is responsible for since 2021. This was ahead of India’s Extended Producer Responsibility, which required companies to collect and recycle 70% of plastic usage in 2023.

There is a distance to go, however: only about 3% of the plastic in HUL packaging is recycled, with a target of 15% by 2025, suggesting the company will continue to introduce virgin plastic for the foreseeable future. This also has a social implication, because poorer Indians still work as waste pickers to help big companies meet their environmental targets, so every change has a knock-on effect. Unlike some other companies we have spoken to, HUL does not duck this issue, openly discussing it and working with the United Nations Development Programme to try and improve the lives of those affected.

Emissions

A company with the scale of manufacturing and distribution of HUL also has to consider the impact of its emissions. HUL has a large manufacturing footprint, owning 29 factories and working with over 50 manufacturing partners that produce 65 billion units globally using materials and services from over 1,300 key suppliers.

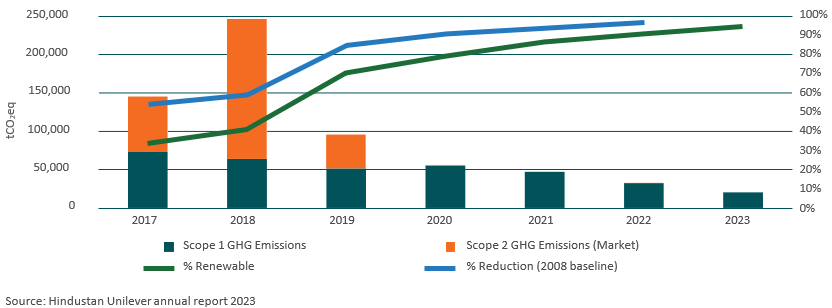

HUL has targets to reduce emissions in its operations to zero by 2030 and achieve net zero emissions from sourcing to point of sale by 2039. It has already made significant and meaningful steps towards achieving these goals, with a 97% decline in emissions intensity per tonne of production volume compared with 2008, and it seems to be accelerating: most of this improvement has come since 2018. This is a direct result of HUL's efforts to fully eliminate Scope 2 emissions9, which it achieved in 2023. All of its electricity comes from renewable sources, with a combination of solar plants and windmills and the purchase of IREC Green Certificates to offset the company’s emissions footprint due to the makeup of India’s grid. Scope 1 emissions10 have also been significantly reduced by eliminating all coal from operations in 2021.

Given India’s national target of net zero for 2070, HUL’s target of 2039 puts it in a significant leadership position, which we believe enhances its reputation.

Figure 2. Hindustan Unilever’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions

Sustainable sourcing

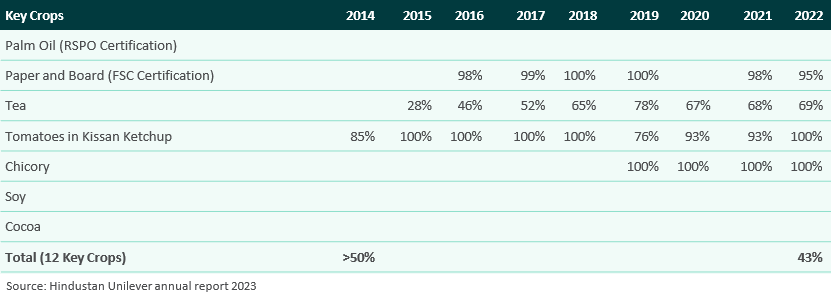

An important target for the whole Unilever ecosystem is the sustainable sourcing of key ingredients; palm oil in particular receives a lot of attention because of its effects on biodiverse habitats. Initially, HUL aimed to source 100% of its agricultural raw materials sustainably by 2020. But in 2022, sustainable sourcing only stood at 43% and HUL’s sustainability goals no longer mention a timeframe for achieving 100% sustainable sourcing. The company also mentions that it is progressing towards its goal of 100% sustainable palm oil, but it fails to report any figures to support this, unlike its parent Unilever, whose figure stands at 90%. HUL acknowledges that it has been difficult to gain full visibility of its supply chain.

Another area of risk is the sustainable sourcing of tea, which currently stands at 69%. This is defined by HUL as certified by the Rainforest Alliance or verified by trustea11, which is a local programme to achieve sustainable tea in India and includes partners like HUL and Tata Consumer. For the remaining 31%, HUL has traceability up to the factory level, but not on the sourcing of the tea by the factory.

Figure 3. Hindustan Unilever’s sustainable sourcing

HUL is in the main addressing its sourcing risks. However, we have some concerns about the omission of a timeframe for these targets and it’s an area we intend to discuss with the management team. No company is perfect. However, there is a risk that the business deprioritises this target, and the lack of a timeframe lowers the pressure for action.

Management oversight

Our analysis also considers the oversight mechanism a company has in place, because this can demonstrate how serious a company is about addressing its sustainability challenges. All too often we see companies adding the designation chief sustainability officer to the existing head of public relations or marketing. By contrast, HUL introduced an ESG committee in 2022, which involves the CEO and independent directors.

We also like to see long-term incentive plans that include sustainability targets. Management at HUL have specific targets for sustainability that drive payouts, such as the percentage of tea sourced sustainably for the director of foods and refreshments.

Conclusion

We believe that behaving sustainably is a key determinant of compounding shareholder value. Increasing scrutiny is gradually making it harder for companies to hide and those that lead the way should see their enhanced reputation reflected in greater intangible value over time and lower long-term business risk.

Recognising and addressing sustainability issues also reduces the risk of governments and regulators levying the external costs of environmental pollution on businesses, so makes existing profit margins more sustainable.

We recognise that there is no such thing as a perfect company so focus on a bottom-up approach that considers materiality and alignment. HUL represents a good example of a company which, although far from perfect, appears to be focusing on the right things and not hiding difficult truths about the challenges it faces. As minority shareholders, we can’t force change in a company like this but we can remind management that we are watching and that we believe this is a critical part of delivering value for shareholders.

1. Financial Times (6 May 2021). ‘Mom-and-pop stores at centre of India’s $850bn retail evolution’. www.ft.com/content/2784a13d-c942-4efe-bc7a-c0b2b9a8fb4c

2. Hindustan Unilever website: www.hul.co.in

3. IFRS Foundation web page on SASB Standards: www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/sasb-standards

4. SASB materiality finder: https://sasb.ifrs.org/standards/materiality-finder/find 5. Reuters (22 June 2022). ‘Unilever’s Plastic Playbook’: www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/global-plastic-uni- lever/#:~:text=Now%2C%20855%20billion%20plastic%20sachets%20are%20sold%20every%20year%2C%20 enough,high%2Dquality%2C%20safe%20products

6. Prahalad, CK (2004). The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid.

7. Hindustan Unilever (25 January 2022). ‘Why do you continue to sell plastic sachets?’ www.hul.co.in/news/2022/why-do-you-continue-to-sell-plastic-sachets/

8. Hindustan Unilever: Waste free world. www.hul.co.in/sustainability/waste-free-world/

9. Scope 2: indirect emissions from purchased energy.

10. Scope 1: emissions that a company directly owns and controls.

11. Find out more on trustea.org